The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (UNDRR 2015) advocates for incorporating Indigenous knowledges and practices to complement scientific knowledge for effective and inclusive emergency and disaster management. Such traditional and local knowledge is an important contribution to developing strategies, policies and plans tailored to local contexts. A comparative analysis of local disaster management plans in Australia was undertaken as part of a larger project on emergency and disaster management in Indigenous communities and was performed to benchmark against the Sendai Framework priorities. A comprehensive search of publicly available local disaster management plans and subplans in selected local government areas was undertaken. Eighty-two plans were identified as well as 9 subplans from a list of Indigenous communities and associated local government areas. This study found a wide disparity in the organisation, presentation and implementation of knowledges and practices of local communities. While some plans included evidence of engagement and consultation with members of local communities, overall, there was little evidence of knowledges or traditional practices being identified and implemented. This analysis was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–21) and most councils had local pandemic management subplans. However, many were not publicly available and targeted approaches for Indigenous communities were not evident on council websites. To reflect the priorities of the Sendai Framework, better consultation with local communities and leaders at all levels of government needs to occur and subplans need to be easily available for review by policy analysts and academics.

Introduction

Historically, First Nations1 peoples' knowledge regarding preparing for, coping with and recovering from disaster events has been overlooked (PAHO & WHO 2014, UNDRR 2015). However, international charters such as the Sendai Framework Priorities for Action (UNDRR 2015) call for the inclusion of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge to complement scientific knowledge in disaster risk management (PAHO & WHO 2014, UNDRR 2015). Specifically, within the Sendai Framework (UNDRR 2015), the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge is highlighted in the Preamble (p.10), Priority 1 (p.15), Priority 2 (p.18) and Priority 4 (p.23).

This paper provides a comparative analysis of local disaster management plans benchmarked against the Sendai Framework directive to incorporate First Nations knowledges in risk management planning. A content analysis methodology incorporating critical theory as a means of revealing equity issues was conducted. To provide context, information on disaster management planning arrangements in Australia and the importance of incorporating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ perspectives were reviewed. As a result, this study calls for action to consult with local communities and Indigenous leaders to ensure relevant local knowledge is embedded in risk planning in Australia.

Background to the research

The Sendai Framework was adopted by Australia and other members of the United Nations to acknowledge the importance of managing disasters and disaster risk. Australia’s National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework 2018 (National Resilience Taskforce 2018) outlines Australia’s commitment to the framework and details policy that reduces disaster risk (Portillo-Castro 2019). Stepping down from the national level, states and territories in Australia have developed local disaster management plans through collaboration with various emergency and disaster management bodies. These plans are informed by risk assessments relevant at the local, district and state or territory levels.

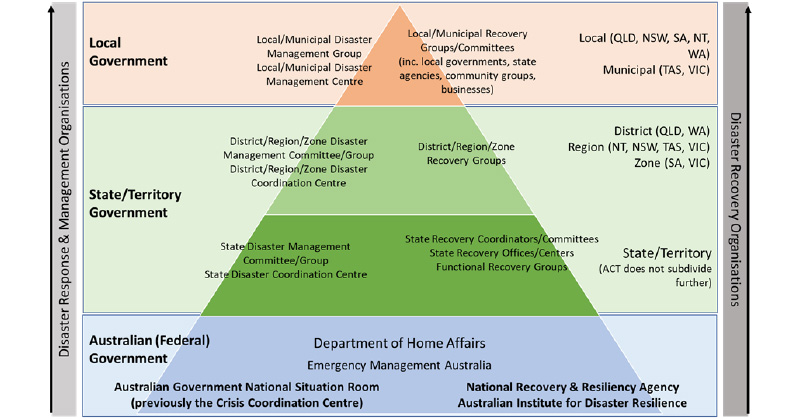

Figure 1 provides an overview of the national, state and local disaster response, management and recovery arrangements at the time of this study. While there are some differences in the procedures and/or governance arrangements, essentially, the state and local structures are based on the national policy outlines.

Figure 1: Australia’s national, state and local disaster management and recovery arrangements.

Source: Adapted from Australian Capital Territory Parliamentary Counsel 2014, Department of Home Affairs 2022, Government of South Australia 2021, New South Wales Government 2018, Northern Territory Emergency Service 2021, Queensland Fire and Emergency Services 2018, Tasmanian Government State Emergency Service 2019, Victoria State Government 2021, Western Australia Government 2021.

At the local level, disaster management plans provide the framework to plan and coordinate capability and operations with the intent to safeguard people, property and the environment. These plans provide information for communities to manage hazard risks, respond to events and be resilient. Subplans, situated within local and/or district management plans, address specific susceptibilities of the region as identified during the risk assessment phase. These detail processes and practices and the activities to be undertaken by disaster management groups or agencies (QFES 2018). It is within the national, state, district and local disaster management plans that the Sendai Framework (UNDRR 2015, p. 15) recommends inclusion of Indigenous knowledges to complement scientific knowledge in disaster prevention, preparation, response and recovery.

Disaster management and First Nations peoples

There has been research in Australia about incorporating localised knowledge into disaster management plans. However, a paucity of information remains concerning implementing practical actions to engage First Nations people (McKemey et al. 2022, Williamson & Weir 2021) in the prevention, preparation, response and recovery approaches to risk management (Sangha, Edwards & Russell-Smith 2019).

To initiate inclusion, international benchmarks suggest focusing on:

- integrating Indigenous perspectives into national policies to provide a strategic framework for action, self-determination and protecting cultural knowledge

- incorporating traditional Indigenous knowledges into national, state and local disaster management strategies and policies, especially as risk reduction tools

- including local communities in the design and implementation of early warning systems to ensure linguistic and cultural relevance

- conducting training programs for youth on technologies that are part of early warning and GIS2 mapping applications, which could include training developed by Elders on how to adapt traditional knowledge to the contemporary context

- highlighting the effects of climate change (PAHO & WHO 2014, UNDRR 2015).

Methodology

This study was part of a larger project to understand hazard risk in rural and remote communities with a high proportion of First Nations peoples and to identify challenges and gaps that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research design used content analysis techniques to unitise, sample, code and reduce the data (Krippendorff 2019, p.88). The data were examined through a critical theoretical lens (Bohman, Flynn & Celikates 2005; Braaten 1991) to uncover and critique the structures and agency for Indigenous community inclusion and engagement in the development and implementation of these. Using a critical theoretical approach allowed for the exploration of the practical and emancipatory qualities of knowledge embedded in the plan to analyse the ‘inter-subjective and in-depth perception of the social world’ (Kendall 1992, p.6). This allowed for the examination of the content for relationships between Indigenous knowledge practices and the public policy texts (Braaten 1991, Kendall 1992).

The study compared a sample of plans and subplans against the Sendai Framework recommendations. Australian local government councils and/or shires that have significant proportions of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander peoples were identified based on a 3-stage process:

- all shires or councils with high percentage populations of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander peoples in Queensland were included

- a list of Indigenous communities and their respective local government areas from the states and territories was compiled from the National Indigenous Australians Agency website

- Australian Bureau of Statistics data (2022) was used to identify local government areas with significant populations of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander peoples.

A final list of 88 local government areas became the research sample. Of those 88, 9 had no publicly available local disaster management plan. In Queensland, the Torres Strait Regional Council and the Torres Shire Council use one common plan. Thus, 78 publicly available local disaster management plans were used for the comparative analysis (see Table 1). A further 4 community Local Emergency Management Arrangement documents from the Northern Territory were included as they directly related to the Territory’s Indigenous communities and were not captured in the local disaster management plans. In addition, 9 pandemic-specific subplans were identified and analysed. Hence, a total of 91 documents were collated as the sample for the critical content analysis.

Table 1: Total number of local disaster management plans used in this study.

| Document type | Number sampled for analysis |

| Plans publicly available | 78 |

| Additional Northern Territory community-specific local emergency management arrangements | 4 |

| Subtotal - number of plans/community local emergency management arrangements | 82 |

| Pandemic subplans | 9 |

| Total - number of plans/community local emergency management arrangement and subplan documents analysed | 91 |

Content analysis was used to determine the presence of certain words, themes or concepts within the data (Krippendorff, 2019). The analysis identified and analysed the presence, meanings and relationships of words, themes and concepts. The content analysis coding and reduction processes examined the plans and subplans for a range of comparison terms and themes as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Key comparative search terms and associated relational themes.

| Indigenous | Knowledge | Community | Culture | Pandemic |

| First Nations | Traditional methods | Community engagement | Cultural considerations | Pandemic risk |

| Aboriginal | Practice(s) | Community consultation | Culturally sensitive approach | Pandemic management |

| Torres Strait | Wisdom(s) | Consultation with Elders |

Results and discussion

The comparative analysis focused on 2 areas:

- Indigenous knowledges: to identify whether the plan incorporated Indigenous knowledges and/or practices.

- Local government pandemic management plans: to identify whether local disaster management arrangements have pandemic management plans including specific considerations for Indigenous communities.

Inclusion of Indigenous knowledges

The critical content analysis revealed no evidence of Indigenous knowledges or practices being incorporated into the plans, in contrast to Sendai Framework recommendations. There was no evidence of mapping or listing of Indigenous practices or traditions nor any arrangements to identify Indigenous ways of managing or recovering from a disaster. As noted by Lambert (2015) and Lambert & Scott (2019), the diversity of Indigenous contexts and knowledges often excludes such knowledges from the ‘boiler-plate’ government documentation that constitutes the framework for response and management of disasters.

While there is consensus on the significance of Indigenous knowledges in managing climate change, coastal area erosion, river basin health, fire practices and sustainable food security, there is also resistance and biases within institutional structures that prevent meaningful change (Lambert & Scott 2019, Parter & Skinner 2020, Shaw et al. 2008). The absence of including Indigenous practices and the lack of acknowledgment of its existence in all plans included in this study is an example of such resistance. Genuine consultation, cooperative discussion and collaborative research are crucial to integrate Indigenous knowledges in modern approaches to disaster management (Ali et al. 2021).

Community consultation, engagement and action

The content analysis revealed numerous mentions of community consultation undertaken while developing local disaster management plans and subplans, but evidence of active community engagement was limited. There were some councils and shires, mainly in Western Australia, where specific Indigenous community consultations were undertaken and ongoing consultation and engagement was noted (this is discussed later).

In other states and territories the situation is less clear. Queensland is unique in that there are discrete Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ councils and shires.3 As such, many of these local government plans recognise local Indigenous contexts as they are administered by Indigenous councillors and local group members. South Australia and Victoria councils and shires included in this analysis mentioned the need for close coordination between disaster management agencies and Indigenous communities to mitigate risk and build resilience. The Northern Territory provides a community-specific local emergency management arrangement instead of council- or shire-based plans. However, in most cases, the plans appeared to be generically drafted rather than tailored for communities and do not present any particular evidence of incorporating local, Indigenous knowledges and practices nor any ongoing community engagement.

Western Australia community consultations

The local disaster management planning structure of Western Australia requires mention in this analysis. Out of the 18 councils and shires included in this analysis, 14 plans specified evidence of community consultations, consultations with Elders as well as mentioning cultural considerations to be undertaken during and after a disaster. Halls Creek Shire and Laverton Shire provided a list of Australian Indigenous languages used in the areas to be considered during planning and response phases. Eleven of the 18 council or shire plans included special considerations for language and cultural requirements for remote communities in the region and also emphasised the use of appropriate communication strategies to reach remote communities. The state’s local disaster management planning documents evidenced greater community engagement and local community involvement compared to other states and territories and provides a good example for community consultation and inclusiveness.

Pandemic management plans

This analysis also looked to identify whether pandemic management plans were available at the local government level in line with the Australian Emergency Management Arrangements Handbook (AIDR 2019) and the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) (Department of Health 2020) recommendations. The pandemic subplans primarily list the structural requirements and departmental responsibilities at the local level and include risk-specific approaches for management. This study shows that most councils and shires had pandemic subplans, however, they were not publicly available and appeared to be internal documents for use within the organisation.

The majority of local disaster management plans analysed included the risk of the pandemic and some had updated information regarding previous pandemics. The risk of various human diseases—Dengue, Influenza, Ebola, H1N1 and COVID-19—were mentioned in most plans and some lessons from past outbreaks were included. Many councils and shires had their pandemic management plans and recovery policies on their websites. However, as with the local disaster management plans, there was no evidence of Indigenous-specific, culturally appropriate pandemic management arrangements or community-focused pandemic management. An example of what to include would be the local arrangements for managing the potential high vulnerability of Elders to disease and how remote communities accommodate and support isolation or lockdown while meeting cultural obligations and practices.

The comparative analysis of pandemic subplans discovered 2 exemplary mentions from South Australia. The Flinders Ranges Council’s pandemic management subplan underlines the need for region-oriented pandemic management and close coordination between local communities.4 Similarly, the Viral Respiratory Disease Pandemic Plan5 for South Australia identifies increased risks for Indigenous communities and notes the need for additional healthcare support for remote communities along with culturally appropriate messaging. These 2 cases show significant steps towards inclusive planning for Indigenous communities.

Recommendations

The following recommendations were drawn from the analysis.

Recommendation 1: Incorporate Indigenous knowledges

Local Indigenous knowledges should be incorporated into all levels of disaster management plans. This requires effective consultation with communities and Indigenous leaders related to appropriate messaging, policy, legislation and documents. Consistent with the UNISDR policy note (Shaw et al. 2008) and discussions, this research suggest steps forward should include establishing a resource group to document and validate Indigenous knowledge in disaster management and policy advocacy to initiate change.

Recommendation 2: Publicly available subplans

Local subplans should be available publicly to assist with localised risk assessment, prevention, preparedness, response and recovery. These subplans need to be written for the community audience they are aiming to support. The subplans need to include First Nations peoples through consultation and engagement to ensure the plans are relevant and effective for specific community contexts. Thus, there is need for consultation and prior preparation to optimise localised disaster management and close coordination with the communities must be undertaken. This study found that while most communities had developed a pandemic subplan, it was done as a reaction to the current pandemic rather in preparation for such events.

Conclusion

This analysis found little evidence of incorporating Indigenous knowledges and practices into local disaster management plans. The lack of inclusion of Indigenous ways was evident in all of the plans analysed. Most of the local disaster management plans appeared to be generically drafted, either within the organisation based on state guidelines or by consultancies rather than being tailored plans that identify and address local requirements and regional and population challenges. There was minimal evidence of close coordination with Indigenous communities when managing a pandemic and the higher risks of pandemic effects on Indigenous communities was not widely recognised in the plans. The findings of this analysis verify that the recommendations of the Sendai Framework are not being met and this underlines the immediate need for action.

This study showed that Indigenous communities use practices and methods to manage a disaster including early warning signs that are often straightforward, sustainable and cost-effective. However, the lack of incorporating Indigenous knowledge and practices into local plans shows the need for urgent action, especially given the increase in the frequency and severity of high-risk hazards. Achieving the equilibrium between science and technology-based disaster management and traditional Indigenous knowledges and practices requires genuine collaboration with Indigenous communities.